The annelids generally have a well-developed coelom that acts as a hydrostatic skeleton: contraction of the muscular body wall against the incompressible coelomic fluid increases the internal pressure, creating stiffness and support. This type of skeleton also provides a means of locomotion; imagine a balloon filled with water (water is incompressible). If you squeeze the balloon at one end, the water must go somewhere, so it stretches the other end out, causing elongation.

Notice, however, that in this type of system there is little control over the movements: the single contraction causes a response along the whole length of the balloon (or worm). Because each segment of an annelid has its own set of circular muscles, and there is partial compartmentalization of the coelomic fluid by septa (infolded walls of tissue), the worm is able to control its movements. Annelids also possess longitudinal muscles at 90° angles to the circular musculature.

Directed elongation of the segments at the anterior end while simultaneously thickening (and anchoring) segments at the posterior end, followed by anchoring of the anterior segments, releasing the posterior segments, and then pulling the posterior end forward, allows the worm to move through the sediment. Phew, quite a long sentence! Try reading that again and imagining the sequence of events. Make a sketch that represents the sequence of events described. Think about when the circular and longitudinal muscles of each segment are in contracted vs. relaxed states, creating a wave-‐like sequence of contraction.

The members of this phylum, particularly the polychaete worms, have different types of life histories.

PHYLUM ANNELIDA

- Coelomate

- Bilateral symmetry

- Protostome development

- Metamerism (segmentation)

- Partial internal compartmentalization of the coelom by septa (except in leeches)

- Setae or chetae

- Closed circulatory system

- Excretion by metanephridia in most species

- Well-defined nervous system (brain and pair of ventral nerve cords)

- Hydrostatic skeleton

CLASS POLYCHAETA marine worms (>5000 spp.); free-‐living; parapodia (found on each side of most segments) and used for locomotion, respiration or feeding; setae located on the parapodia; dioecious (separate sexes); head often well-‐ developed; trochophore larva

CLASS OLIGOCHAETA includes earthworms (~3000 spp.); terrestrial or freshwater; no parapodia; short setae; monoecious (hermaphroditic); clitellum, a thickened area mid-‐body that secretes mucus and is used for sperm exchange; reduced head

CLASS HIRUDINEA leeches (~300 spp.); mainly freshwater, few marine and terrestrial in moist, warm areas; no parapodia or setae; hermaphroditic; clitellum present; suckers at anterior and posterior ends; ectoparasitic; carnivorous or detritivores (feeding on decaying matter); some leeches are free-‐living (not parasitic); coelom reduced—coelomic space virtually filled with connective tissue

Polychaeta

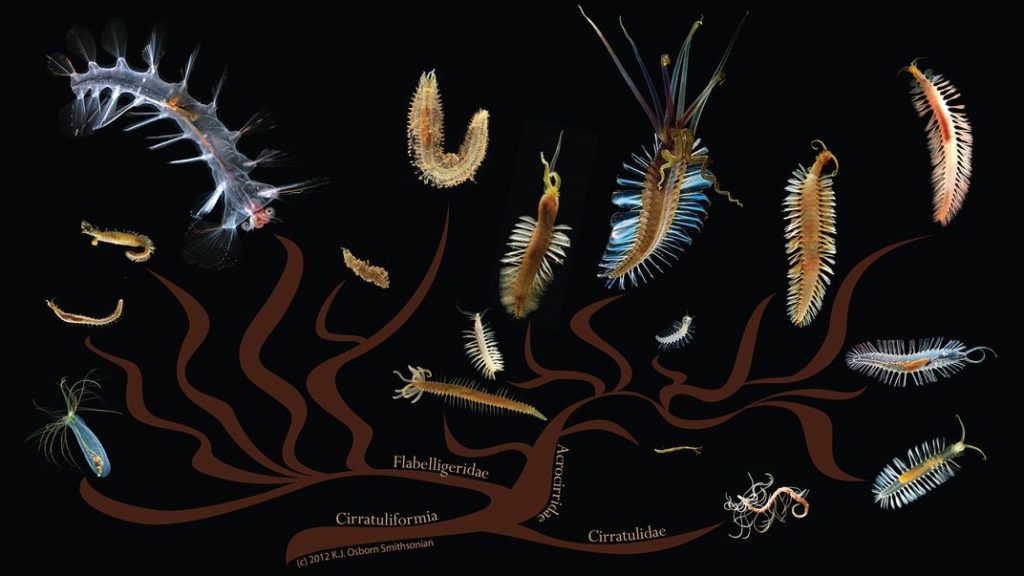

There is a great diversity in Polychaete worms, including tremendous variation in body form, much of it associated with feeding/trophic adaptations. This, of course, may result in intense selective pressure.

Observe and describe the morphological differences between the various species of polychaete worms shown in the video.

- For at least three of the specimens shown, describe their morphological features, their means of locomotion, and the habitat in which they live.

- Why is the Class Polychaeta a good example of an evolutionary adaptive radiation?

Class Oligochaeta

View the video below to investigate the anatomy of an earthworm. As you watch:

- Draw the overall external structure of the worm and label:

- Mouth

- Ventral midline

- Sperm groove (if present(

- Clitellum

- Draw the overall internal structure. Your sketch should include these major systems:

- Digestive system: pharynx, esophagus, crop, gizzard, intestine

- Circulatory system: dorsal and ventral blood vessels, pumping vessels/heart

- Excretory system: metanephrida

- Reproductive system: seminal vesicles

- Nervous system: cerebral ganglia, ventral nerve cord